Home Page

The latest articles, features and news.

Read About...

|

| | |

|

29 January 2007

The Testicle Transplant Craze

The War On Erectile Dysfunction - Part IV

by Paul Aitken

In the summer of 1999, wire services trumpeted news of an unorthodox operation that was due to be performed on a young cancer patient. The boy was about to undergo chemotherapy which would kill the germ cell progenitors of his future sperm rendering him permanently infertile. The bold surgical plan was to remove one of his testicles prior to chemotherapy, preserve it cryogenically and re-transplant it after the chemotherapy was finished, thus restoring his fertility.

In the summer of 1999, wire services trumpeted news of an unorthodox operation that was due to be performed on a young cancer patient. The boy was about to undergo chemotherapy which would kill the germ cell progenitors of his future sperm rendering him permanently infertile. The bold surgical plan was to remove one of his testicles prior to chemotherapy, preserve it cryogenically and re-transplant it after the chemotherapy was finished, thus restoring his fertility.

The papers touted this as the "first ever testicle transplant." They were wrong about this in two respects: 1) This was technically not a transplant, it was a re-plant; and 2) It wasn't the first, not even close. According to citations in medical literature, the first testicle transplant was performed by Dr. Sherman Silber, in 1977, between identical twins. And it was successful as it turned out; as the recipient later fathered four children (his brother's technically). In fact, both the wire services and the medical literature were wrong, and their claims betray a collective amnesia over what has to be one of the most sensational and regrettable episodes in medical history.

The first testicle transplant was in fact performed on roosters by the German physiologist, Arnold Berthold, in 1848. Berthold castrated six male birds and noticed that the birds lost their plume, their aggressive tendencies and all interest in Henhouse magazine centerfolds. He then re-implanted the testicles in two of the birds and in two others, transplanted donor testicles from the last two birds. All four re-testiclized roosters regained their strut and resumed their roosterish ways. Although his experiment was ignored for half a century, Berthold is now held in high regard as the father of modern endocrinology.

The first recorded human transplant was performed in Philadelphia in 1911 by Drs. Levi Hammond and Howard Sutton. The recipient was a 19 year man who had been kicked in the balls. The donor was another young man who had recently bled to death (the alternative would have been a sheep, apparently). Not surprisingly, given the lack of knowledge of immune system functioning at the time, the organ was rejected and the episode was largely forgotten.

But the granddaddy of testicle transplants, the man who truly deserves primacy in this questionable field, was a Chicago urologist by the name of Victor Lespinasse. Lespinasse's operations and their reported success ignited a flurry of testicle transplants in the early 1920s in what has to be one of the weirdest episodes in medical history.

Lespinasse's first transplant patient was a 33 year old man who had the misfortune of losing both testicles independently. The first was lost in a botched hernia operation, the second after an accident. After the loss of the second testicle, the man found he was unable to perform sexually and sought Lespinasse's help in January of 1911. Operating under the assumption that the testicles were the source of masculine vigor, Lespinasse performed the first ever testicle transplant in 1911, three months earlier than the Hammond/Sutton procedure, but he didn't write about it until 1914 (it's "snooze, you lose" in the world of scientific accreditation).

Rather than transplant the donor testicle intact (it was believed to have been purchased from some poor sap who needed the dough), Lespinasse grafted testicle slices (theory being that thin slices would more likely fuse to the existing tissue and not be rejected) in the scrotum and rectus muscle. According to Lespinasse's reports, four days after the operation the recipient reported a strong erection and checked out of the hospital to put it to good use. After a follow-up two years later, Lespinasse reported that the man's virility remained intact. Rather than transplant the donor testicle intact (it was believed to have been purchased from some poor sap who needed the dough), Lespinasse grafted testicle slices (theory being that thin slices would more likely fuse to the existing tissue and not be rejected) in the scrotum and rectus muscle. According to Lespinasse's reports, four days after the operation the recipient reported a strong erection and checked out of the hospital to put it to good use. After a follow-up two years later, Lespinasse reported that the man's virility remained intact.

While it's certainly possible that the Lespinasse's patient did indeed experience a testosterone surge in the days following the tissue implantation (remember Berthold's roosters), given what we know about the workings of the immune system, the effects were likely short-lived. If Lespinasse himself had reservations about the long term prospects of his procedure (he later wrote that it was impossible to separate the effects of the testicular grafts from the "strong mental stimulus engendered by the operation"), he nevertheless continued to perform and champion the procedure. In 1922, Lepinasse performed the surgery on Harry F. McCormick, one of the richest men in the world at the time and the subject of much tabloid gossip. Such was his fame that the procedure made the front page of the New York Times. The donor was reputed to be that exemplar of maleness, a blacksmith, inspiring the ditty:

Under the spreading chestnut tree,

The village smithy stands,

The smith a gloomy man is he,

McCormick has his glands

Lespinasse's reported successes encouraged others to follow. An early enthusiast was Leo L. Stanley, the chief surgeon at San Quentin Prison who performed the operation on geriatric prisoners (volunteers, of course). Stanley theorized that tissue obtained from negroes would have a greater concentration of "virilizing essence" and preferred to use black men as donors. Luckily, he had an abundant supply: executed prisoners.

By the early 1920's, testicular transplantation was the impotence therapy of choice for men with soft dicks and hard cash. Much of this, it must be said, was driven by wishful thinking. People really wanted this to work, none more so that the patients themselves. After all, they had submitted to the procedure and likely paid handsomely for a donor to offer up a gonad. Nobody wanted to admit being a sap. As a result, the reported successes were numerous and failures few. Like stock market bubbles and magnetic therapy, testicle transplantation was an empty fad that fed off itself. People got caught up in the optimism as did the doctors who performed it. In 1920, Dr. G. Frank Lydston, a colleague of Lespinasse and one of the leading practitioners of testicle transplantation, had the procedure performed on himself. If nothing else, the success of testicle transplantation in the 1920's is a testament to the powers of the placebo affect.

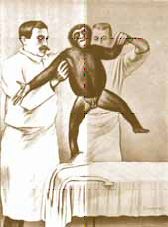

At about the same time, across the Atlantic in Paris, a Russian surgeon named Serge Voronoff came up with a brand new testicular procedure. The technique was the same, essentially the one practiced by Lepinasse, the big difference was that the donors were chimps. This was partly out of convenience, partly because Voronoff thought it unethical to "remove the source of vigor from a young man for the sake of making an old man young." But mostly it was out of an unerring instinct for self-promotion. While there is no doubt that Voronoff fully believed in the rejuvenating powers of "monkey grafts", he will be remembered as one of the greatest hucksters in medical history. At about the same time, across the Atlantic in Paris, a Russian surgeon named Serge Voronoff came up with a brand new testicular procedure. The technique was the same, essentially the one practiced by Lepinasse, the big difference was that the donors were chimps. This was partly out of convenience, partly because Voronoff thought it unethical to "remove the source of vigor from a young man for the sake of making an old man young." But mostly it was out of an unerring instinct for self-promotion. While there is no doubt that Voronoff fully believed in the rejuvenating powers of "monkey grafts", he will be remembered as one of the greatest hucksters in medical history.

Voronoff actually performed the operation with donor and recipient side by side, both stretched out on the table with their nuts hanging out. Needless to say, the recipient was the only one there out of choice. By all accounts it wasn't fun for the chimps, who had to be caged and gassed prior to the procedure.

This was shock-science and Voronoff's experiments received a great deal of attention internationally. At first, the scientific community was horrified by the thought of xenotransplantation. But when Voronoff screened films of the procedure, as well as before and after footage, to audiences around the world, he slowly won them over. In his films, men who were clearly in the advanced stages of decrepitude were shown months after the operation riding horseback, rowing and doing other manly athletic feats. The films didn't show any great strapping erections, but Voronoff made it clear that his operation rejuvenated the recipients sexually as well. In 1923, Voronoff was given a standing ovation by 700 doctors at the International Collage of Surgeons.

Voronoff's fame spread throughout Europe and North America, convincing Leo Stanley to give up on executed prisoners and move on to apes. Stanley went on to perform 300 testicle transplants using apes. Such was the popularity of the procedure that it inspired the pulp novel The Gland Stealers, and a cocktail drink called the Monkey Gland, which supposedly imparted some of the same rejuvenating effects. The French Government even had to pass a law banning monkey hunting in its African colonies.

What is perhaps most remarkable about this whole sorry episode is not that the procedure became widespread, but that it endured for so long. For a period of over 15 years, nobody seriously questioned the efficacy of the procedure. It all came to an end in 1929, however, when Henri Velu, a French veterinarian, conducted microscopic analysis of his own grafting experiments and found that the tissues had been completely rejected. He concluded that testicle grafts were "Une grande illusion." Other scientists confirmed Velu's conclusions and monkey grafts eventually fell out of favor.

Over the course of his career, Voronoff supposedly performed more than a 1,000 operations. And at fees of upwards of $5,000 a pop, he was certainly one of the richest doctors in the world. Yet he lived to be a tragic figure. He had genuinely believed in his procedure and was horrified at the thought that his grafts may have introduced simian diseases into their hosts. Voronoff, died broken-hearted in 1951; in the end, just a prurient footnote in medical history.

|

|